Richard Morrison: Dyb, dyb, dyb — the scouts and guides culturally enrich young lives

I live in a London borough where 763 knife crimes were recorded last year. And we don’t even have the distinction of being the capital’s most violent area. Even so, it’s a rare week that the local paper doesn’t report a horrific stabbing, usually involving people in their teens.

Last week, however, the youngsters of the London borough of Brent made headlines for a happier reason. A new scout group has been started in Willesden, just up the road from me, and it’s symbolic of a remarkable turnaround.

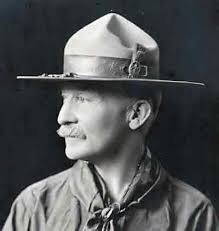

In the 1960s, when I joined the cubs, Willesden had more than 40 scout troops. By the early 2000s just a handful were left. Scouting seemed doomed. The battle to keep children out of mischief by teaching them life skills — which was Robert Baden-Powell’s main objective when he founded the scouts in 1908 — appeared lost. Gang culture was rife. In truth it still is, but there has been a great fightback by the scouts, especially in areas most in need of youth activities. Since 2014 more than 20,000 members have been recruited and 1,200 groups set up, including 222 in Britain’s most impoverished communities.

They range from Byker in Newcastle and Wythenshawe in Manchester, to Jaywick on the Essex coast — officially “the most deprived town in England”. For a movement written off as irredeemably white, middle class, dated and tainted, this renaissance has been astonishing.

What has driven it? There has been dynamic leadership, notably from the TV action man and former SAS soldier Bear Grylls, the youngest chief scout in history when appointed in 2009. And the scouts have also received useful funding from the government-backed Youth United and the Pears Foundation, a charity set up by the multibillion-pound William Pears property group. That has enabled the launch of exciting initiatives, though all focused on Baden-Powell’s basic principle of nurturing responsible, resilient and resourceful young people.

There are still challenges. One is the legacy of past traumas. Last month newly released files kept by the Boy Scouts of America revealed that, since the First World War, nearly 8,000 American scout masters have been accused of sexual abuse. We don’t have figures for the UK, yet nobody believes that this is exclusively an American problem.

Safeguarding procedures are now rigorous. Despite that, or maybe because of it, people who volunteer to work with children still sometimes feel that their motives are being tacitly questioned. That and the sheer hassle of getting DBS-checked are surely reasons that scouts and guides are chronically short of adult leaders. Then there’s the turf war between scouts and guides. In the UK it’s not as bitter as in the US, where the girl scouts are suing the boy scouts for trademark infringement after the latter announced that they were dropping the “boy” from their name and admitting girls.

Nevertheless, the UK’s guides (now called Girlguiding) were clearly not pleased when the Scout Association became fully coeducational in 2007, thus poaching thousands of girl recruits. The response, however, has been invigorating. Girlguiding has become (in the words of its former chief executive Julie Bentley) “the ultimate feminist organisation”. It has led anti-sexist campaigns, such as for girls to get more opportunities to play traditional “male” sports, including cricket, football and rugby at school. And, more controversially, it has set up a partnership with the British Army to teach girls leadership skills.

The truth is that both organisations are making commendable attempts to be relevant. There’s a strong emphasis on green issues now (only last week the cub scouts launched an “environmental conservation activity” badge). Yet the 200-odd activity badges also include painting, the performing arts and such modern topics as computer coding, body confidence, media critic (“analysing media stories for bias”) and protesting. The Daily Mail doesn’t like it (always a good sign), but the children do.

Yes, they still go camping — almost an alien experience for many urban youngsters. And they still wear uniforms, although the guides have had three makeovers in 30 years (most famously by the designer Jeff Banks in the 1990s) and the scouts are promising a redesign.

In any case, are uniforms so bad? Baden-Powell insisted on them not for militaristic reasons (the war hero who defended Mafeking became very pacifist later in life), but because they hid differences in class and wealth. Those differences haven’t gone away. Uniforms also create a sense of belonging, and that’s even more important today. One big reason why children drift into gangs is because if they have been excluded from school, alienated from their parents and feel they have no stake in society; there’s a vacuum in their lives where validation should be. Scout and guide groups can fill that in an entirely positive way. At a time when cash-starved local authorities are cutting or abolishing youth services, the resurgence of these volunteer-led organisations is all the more heartwarming.

Dyb, dyb, dyb, say I — even if nobody under 40 has the foggiest idea what that means.

It’s soft-headed to dismiss arts A levels

Research by the Royal College of Music has revealed — surprise, surprise — not just a dramatic decline in the number of students taking A-level music, but also vast regional disparities, with poorer areas offering children significantly fewer opportunities to study music. Last year there wasn’t a single A-level music entrant in the whole of Middlesbrough.

It’s not just about money. Music, drama and art are still stigmatised as “soft” subjects by the educational establishment, leading pupils and parents to believe that studying them is a waste of time. Thank goodness, then, that the Russell Group of universities has belatedly decided to scrap its deplorable list of “facilitating subjects” — a list that excluded arts A levels, thereby giving the impression that they wouldn’t be counted when assessing applications for undergraduate courses.

Now the government must follow suit: scrap the EBacc curriculum that marginalises arts subjects and let state schools offer the same broad, balanced education as is available to children whose parents can afford private-school fees.